Scholars are still unsure why American cities passed cross-dressing bans over the closing decades of the nineteenth century. By the 1960s, cities in every region of the United States had cross-dressing regulations, from major metropolitan centers to small cities and towns. They were used to criminalize gender non-conformity in many forms - for feminists, countercultural hippies, cross-dressers (or “transvestites”), and people we would now consider transgender. Starting in the late 1960s, however, criminal defendants began to topple cross-dressing bans.

The story of their success invites a re-assessment of the contemporary LGBT movement’s legal history. This article argues that a trans legal movement developed separately but in tandem with constitutional claims on behalf of gays and lesbians. In some cases, gender outlaws attempted to defend the right to cross-dress without asking courts to understand or adjudicate their gender. These efforts met with mixed success: courts began to recognize their constitutional rights, but litigation also limited which gender outlaws could qualify as trans legal subjects. Examining their legal strategies offers a window into the messy process of translating gender non-conforming experiences and subjectivities into something that courts could understand. Transgender had to be analytically separated from gay and lesbian in life and law before it could be reattached as a distinct minority group.

Type Original Article Information Law and History Review , Volume 40 , Issue 4 , November 2022 , pp. 679 - 723 Creative CommonsThis is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Copyright © The Author(s), 2023. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of the American Society for Legal History

In the early afternoon of March 24, 1964, John Miller was approaching his home on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. He had just crossed the intersection of West End Avenue and Ninety-First Street when a police officer stopped him and asked his name. When he replied “Joan Miller,” he was taken into custody. Footnote 1 Miller, later described by The New York Times as a “tall, burly man of 58,” was a father with a military record. Footnote 2 He was also a transvestite, or cross-dresser, which meant that he enjoyed dressing as a woman. Footnote 3 His crime was violation of Section 887(7) of New York State's vagrancy law, by then over a century old, which made it illegal to appear in public with one's “face painted, discolored or concealed, or being otherwise disguised, in a manner calculated to prevent. . . being identified.” Footnote 4 While the law did not explicitly reference clothing, police often used it to punish cross-dressing, and courts usually accepted that interpretation. Most of the time, people arrested under such laws did not mount expensive legal defenses, and those who did rarely appealed past the trial court level.

John Miller was different. Yes, like many gender outlaws before him, he could not afford to mount a legal defense. Footnote 5 In fact, his arrest cost him his job. But Miller had advantages that his predecessors did not: he could turn to a community of other transvestites through new networks of identification and support. Miller was on the guiding council of Full Personality Expression (FPE), one of the earliest social and political organizations for transvestites, whose reach eventually encompassed much of the United States and parts of Western Europe. Footnote 6 The organization pledged $300 to his cause. Footnote 7 Miller also broadcast requests for financial support in Transvestia and Turnabout, two early transvestite publications, and received at least seventy contributions from the United States, Canada, and England. Footnote 8 The geographic range of this support reflected both the broad scope of the emerging transvestite network, and the community's shared desire to challenge cross-dressing regulation. As one donor from Texas put it in a quick note with his contribution, “We need to get rid of these damn laws.” Footnote 9

Laws banning cross-dressing were ubiquitous in urban America by the middle of the twentieth century. Most were more explicit than New York's Section 887(7), like the law in Columbus, Ohio, which criminalized any person who “shall appear upon any public street or other public place . . . in a dress not belonging to his or her sex.” Footnote 10 Starting in the late 1960s, however, criminal defendants began to successfully undermine cross-dressing bans in a range of cities, from New York and Los Angeles to Toledo and Champaign-Urbana. Footnote 11 Hoping to challenge their arrests, these defendants argued that anti-cross-dressing laws were facially unconstitutional, or unconstitutional as applied to them. As their successes mounted, gender outlaws began to bring civil lawsuits against cities to enjoin them from enforcing their anti-cross-dressing ordinances, marking a shift from the defensive posture of the criminal defendant to the offensive posture of the civil litigant. By 1980, criminal defendants had successfully challenged cross-dressing arrests in at least sixteen cities, introducing many courts to transvestite and transsexual people in the process.

To the extent that historians have addressed the decriminalization of cross-dressing, they have understood it as an adjunct to a broader attack on vague municipal laws. Footnote 12 This article restores the anti-cross-dressing cases to their place within the LGBT constitutional narrative. In that story, the campaign to decriminalize sodomy looms large. Substantive due process rights to sexual privacy and equal protection for sexual and gender minorities became the primary constitutional vehicles for vindication of LGBT rights and full sexual citizenship, culminating in the Supreme Court's endorsement of same-sex marriage in 2015. Footnote 13 By reconstructing the disjointed efforts to repeal anti-cross-dressing laws across the country, this paper points to the multiplicity of legal paths for constitutionalizing gender non-conformity in the early days of LGBT constitutional litigation.

The challenges also bring into focus a distinct legal movement of gender outlaws. Although they were not centrally coordinated, gender outlaws across the country developed their own legal strategy to decriminalize cross-dressing, and in some cases, constitutionalize protections for gender non-conformity. They did so in an era before legal nonprofits organized a cohesive gay and lesbian legal agenda, before that group added transgender legal issues to the mix, and indeed before the identity category “transgender” was in wide circulation. Footnote 14

Historians of LGBT law in this period tend to emphasize how gay and lesbian “homophile” activists of the 1950s and 1960s promoted the idea that homosexuality was an identity rather than stigmatized conduct or medical pathology. Footnote 15 In their efforts to organize against police harassment, they drew inspiration from the Black civil rights movement to portray homosexuals as an oppressed minority group. Footnote 16 Despite changes in medical taxonomy and self-identification, police and courts did not easily differentiate between sexual orientation and gender identity.

For homophile activists, that was part of the problem. To make the analogy sympathetic, they distanced their politicized homosexual identity from its former bedfellows—gender inversion, racial impurity, sex work, poverty, and crime. Footnote 17 Their legal strategy reflected that analysis from the beginning as they mobilized gay identity to articulate a gay legal subject with protected rights to assemble, have sex, organize on campuses, work, and form families as gay people. Footnote 18 Those campaigns laid the groundwork for the constitutional arguments most associated with the contemporary LGBT movement: sexual privacy and the civil rights of “discrete and insular minorities” under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Unlike many gay rights legal claims of the same period, challenges to cross-dressing bans often succeeded without analogizing gender non-conformity to identity-based minority groups. The split in legal claims mirrored social transformation on the ground. Gender outlaws entered courts amid a major shift in how medical authorities and social groups understood the relationship between sexuality and gender, an epistemic change that Joanne Meyerowitz has called the “taxonomic revolution.” Footnote 19 In these formative years of movement and identity consolidation, gender outlaws strategically deployed and obscured their identities, exploiting confusion about gender-bending and playing off of courts’ ignorance.

In some cases, challengers attempted to introduce the legal system to transvestites, transsexuals, and drag queens without closing the door on other gender outlaws. These efforts met with mixed success: courts began to recognize constitutional rights, but litigation also limited which gender outlaws would benefit. Footnote 20 Some challengers sought to expand personal freedoms to include gender expression through clothing, but others yoked trans civil rights to medical authority, defining the trans legal subject as a person seeking medical treatment for pathologized transsexualism. Examining their legal strategies offers a window into the messy process of translating gender non-conforming experiences and subjectivities into something that courts could understand. It also emphasizes the role of legal institutions, alongside social life and medical discourse, in shaping the analytical categories of gender. Footnote 21 Over time, one strand of gender outlaw experience consolidated and became legible to courts as a rights-bearing subject, which I call the trans legal subject.

Three tactics typify the overall strategy. First, gender outlaws challenged cross-dressing bans for vagueness, inviting courts to invalidate the laws without asking judges to adjudicate, or even understand, their gender identities at all. Footnote 22 In a second set of challenges, lawyers argued that cross-dressing was a form of expression protected by the First and Fourteenth Amendments. Under this theory, cross-dressing conduct could be protected regardless of the defendant's gender identity. In a final set of cases brought under the Eighth Amendment, lawyers did make claims based on a consolidated sense of identity, telling courts that cross-dressing was a treatment for medically diagnosed transsexuality. Footnote 23

Many historians have noted the salience of gender non-conformity in anti-homosexual policing in the decades following World War II. Footnote 24 But such policing was not limited to gays and lesbians, precisely because homosexuality was not thought apart from other stigmatized behavior. Police targeted a broad range of activities, which Emily Hobson has called “street life,” including Black and Brown youth culture, “homosocial contact among working-class men, homosexuality and gender transgression, sex work, and interracial contact of various kinds.” Footnote 25 Homophile activists believed that social inclusion and legal recognition required a more respectable image. Footnote 26 Many histories build from this foundation by following the homosexual once he was shorn of his seedier associations, leaving the subject of gender non-conforming policing both widely remarked upon and relatively under-studied. Footnote 27

This article asks what happened to the gender outlaws who did not, could not, or would not see themselves in the new homosexual political identity. The answer reveals early constitutional arguments that gender non-conformity deserved protection on its own terms. It also invites a reconsideration of the contemporary LGBT legal movement. Legal histories often describe a gay and lesbian civil rights movement emerging from the ashes of gay liberation in the early 1970s, and only adding the “T” to LGBT in the 1990s. Footnote 28 Returning to the history of the late 1960s and 1970s, however, suggests an alternative periodization in which campaigns for trans and gay civil rights sprouted from the same root, and grew in parallel. Footnote 29 Transgender had to be analytically separated from gay and lesbian in life and law before it could be reattached as a distinct minority group.

The cases described in this article form a fractured archive of roughly thirty legal challenges from 1963 to 1986. They are national in scope, arising primarily in the West, Midwest, and Northeast, with some appearances in Texas and Florida. About two-thirds appear in published case reporters that include important details such as the names and affiliations of the attorneys and, in some cases, their written submissions. Other cases come from print media, mostly within gay, lesbian, transvestite, transsexual, and drag publications. The level of detail varies significantly, making it difficult to generalize about the attorneys who brought these cases or the arguments they raised. Regional branches of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) made several important contributions, as did the national office after 1973, and one significant case was brought by a legal clinic at Northwestern University School of Law. Footnote 30

Despite these limitations, this article tells a new story. Gender outlaws and their lawyers drew on the popularity of unisex clothing, movements for free expression, and emerging medical discourses on gender identity to argue that cross-dressing could be a benign fashion choice, a protected expression, or a necessary medical treatment for transsexuality. Their successes helped topple cross-dressing regulation in cities and towns across the country, but not without ambivalent results for gender outlaws on the whole. In order to make gender non-conformity legible to the legal system, lawyers translated the diverse array of gender outlaw experiences into a distinctly trans legal subject, defined by medicalized trans identity. Out of disjointed legal defense of gender outlaws emerged a transgender legal movement.

Scholars are still unsure why American cities passed anti-cross-dressing laws. Footnote 31 St. Louis appears to have been the first place to do so in 1843, and Miami may have been one of the last in 1952. No comprehensive national survey has yet been conducted, but we know that at least seventy municipalities and several states in every region of the country had cross-dressing regulation by the 1960s. Their coverage ranged from major metropolitan centers such as Chicago and Los Angeles to small cities and towns including Cheyenne, Wyoming and Vermillion, South Dakota. Footnote 32

The most common ordinances criminalized any person who “shall appear upon any public street or other public place . . . in a dress not belonging to his or her sex.” Footnote 33 Some towns only penalized cross-dressing “with intent to conceal his or her sex,” as in Chicago, or prohibited cross-dressing with intent to commit a crime, as in San Diego. Footnote 34 In cities such as Detroit and Miami Beach, ordinances specified only that men could not wear women's clothes in public. Footnote 35 Each code was different, but these ordinances were generally passed under the municipal police power, a strong legal doctrine with hazy boundaries, which enabled cities to pass regulations affecting the health, safety, morals, and welfare of their citizens.

Although gaps in our records make it difficult to generalize, most prohibitions were passed in the forty years bookending 1900. Footnote 36 Antebellum America churned with social and economic upheaval as young people flocked to cities for work. Footnote 37 White upper-class anxiety about the changing urban landscape prompted legal responses to protect their values and social position, including tighter restrictions on immigration at the federal level, as well as new state restrictions on interracial marriage. Footnote 38 At the city level, vagrancy laws and other municipal morals regulations proliferated. Footnote 39 Considered alongside laws against prostitution, sexual deviance, and public indecency, cross-dressing bans likely disbursed across the country as part of a broader attempt to impose upper-class white Christian morality on the new urban masses. Footnote 40

Fear of sexual and gender deviance may have also motivated cross-dressing regulation. Reports of “passing women” serving in the Union and Confederate armies made headlines nationwide in the years after the Civil War and accompanied accounts of women continuing their “gender fraud” to support themselves in men's jobs. Footnote 41 Similar stories about cross-dressing men in the American West stoked fears of social chaos on the frontier. Footnote 42 Regulating gender deviance may have been an attempt to thwart nineteenth-century feminist dress reformers who politicized Victorian fashions as a symbol of women's subordination and fought to wear bloomers in public. Footnote 43 As Clare Sears has argued in her close study of nineteenth-century cross-dressing regulation in San Francisco, such laws were “central to the project of modern municipal government.” Footnote 44

Anti-masquerade laws, like those in California and Cincinnati, did not mention clothing at all, and likely have separate lineages. New York's statute, for example, arose in response to the anti-rent movement that roiled the Hudson Valley from roughly 1839 to 1865. The movement demanded reform of the rent and property systems governing the region's large estates through anti-rent associations, a political party, and organizations of vigilantes known as “Indians.” Footnote 45 These militant men famously adopted a costume of calico dresses and large leather face masks. Footnote 46 In response, the state government passed an anti-mask law, Section 887(7) of the New York Code of Criminal Procedure, the same law that ensnared John Miller.

Texas's anti-masquerade law may have been a response to a different form of vigilante violence. In 1925, the state legislature passed an anti-masquerade law, including among the offenses “[t]he parading of any secret society or organization or a part of the members thereof, when masked or disguised upon or along any public road, or any street, or alley of any city or town of this state.” Footnote 47 The law may have been intended to target the revived Ku Klux Klan, which grew significantly in Texas in the 1920s. Footnote 48 A fuller accounting of the origins and coverage of cross-dressing laws remains to be written. Footnote 49

Another genre of cross-dressing regulation emerged in the wake of Prohibition. Many states passed new liquor board regulations designed to prevent bars and restaurants from becoming “disorderly” by prohibiting various “persons of ill repute” from congregating there. Footnote 50 Although most new statutes did not mention homosexuality or cross-dressing, liquor officials interpreted their mandate to include regulating gender and sexual deviance. Footnote 51 New Jersey's liquor board explicitly prohibited licensed bars from hosting “female impersonators.” Footnote 52 During World War II, the military also directed significant resources toward controlling vice at home. Footnote 53 These new regulations and enforcement institutions meant that gender outlaws in major cities had several (sometimes competing) authorities to contend with: the police who enforced local ordinances, the liquor agents who enforced bar license regulations, and the military officials empowered to conduct bar raids of their own.

If historians know very little about the origins of cross-dressing laws, we know a bit more about their enforcement. They appear frequently in gay and lesbian legal histories of “anti-homosexual policing.” Footnote 54 One of the challenges of this literature has been reconstructing an ontology of gender and sex that is quite different from our own. Nineteenth-century medicine used the term “sexual inversion” to encompass gender deviance in many forms, including homosexual desire. Footnote 55 Only at the turn of the twentieth century did sexologists begin to differentiate same-sex attraction from gender non-conformity, but in social practice and popular representation, they remained (and remain) deeply interconnected. Footnote 56

Well into the 1930s, the popular press and liquor officials understood gay men to be a “third sex,” or “fairies” whose same-sex attractions were visible in their effeminate gender presentation. Footnote 57 As Anna Lvovsky explains, liquor officials thus conceptualized “homosexuality and gender inversion as twin sides of the same pathology.” Footnote 58 Military authorities focused on “female impersonators” during anti-vice campaigns in Atlantic City, Detroit, and San Francisco during the summers of 1942 and 1943; liquor agents also regularly relied on evidence of bar patrons’ appearance—that men were wearing rouge or lipstick, or that women were wearing men's clothes—to prove that the establishment was a gay bar. Footnote 59 Bar owners attempted to differentiate between homosexuality and the fairy in the 1930s, but without much success. Footnote 60

Those arguments found sympathetic ears twenty years later. Efforts to analytically distinguish homosexuality from heterosexuality based on sexual object choice irrespective of gender presentation date further back, but the idea of a gay political identity was born in the “homophile movement,” the first wave of gay and lesbian political organizing. These groups convened in response to police harassment and developed a public-relations and legal strategy undergirded by a sense of consolidated gay and lesbian identity. Footnote 61

Consider, for example, two canonical early cases in the history of gay civil rights. The first began in 1949 when the California State Board of Equalization moved to revoke the liquor license of a prominent San Francisco gay bar. The proprietor argued that the presence of gay patrons in his bar could not sustain the charge that he was keeping a “disorderly house.” The Supreme Court of California agreed, holding that the regulations were meant to prevent illegal or immoral conduct and could not limit the right of free assembly based on gay status. Footnote 62 No less famous in queer history is the arrest of Dale Jennings in 1952 for cruising. Jennings was a founder of the first homophile organization in the country, the Los Angeles Mattachine Society, and he, too, pressed the distinction between conduct and status in defense of his civil rights as a gay man. He told the jury that he was indeed homosexual but protested that he had not broken the law. Footnote 63 The jury could not reach a verdict, and the charges were dropped. Footnote 64 These examples show how homophile activists differentiated gay identity from criminalized behavior, including public, commercial, underage, and non-consensual sex, as well as gender non-conformity. Footnote 65 Cleansing the image of the homosexual was a key tactic in early attempts to secure gay civil rights. Footnote 66

As homophile activists continued to bring this concept of homosexuality to court, cross-dressing regulation continued apace. A snapshot of anti-cross-dressing law enforcement in the single year of 1972 demonstrates the diverse array of gender outlaws who continued to be caught up in these laws. It also helps illuminate the continued association that police officers made between cross-dressing and homosexual effeminacy, sex work, and gender “fraud.” Sometimes police interrupted drag performances inside clubs, as in Memphis when four men between the ages of 19 and 24 were arrested “for impersonating females” inside a lounge bar where they were “singing and dancing in women's dresses and wigs, kissing one another and kissing customers.” Footnote 67 In Lexington, Kentucky, police initially arrested four performers for go-go dancing in violation of a local morality law, only to “discover that the women were female impersonators” and rebook them for “wearing disguises.” Footnote 68 Cross-dressing bans also formed part of police anti-prostitution arsenals, as in San Francisco, where “forty-one men in drag were arrested. . . . between midnight and 2am” in the city's red light district for “obstructing the sidewalks and wearing women's clothing with intent to deceive.” Footnote 69 The ordinances were one legal tool in a broader constellation of local morals regulations.

Cross-dressing bans were also enforced without suspicion of other crimes. In these instances, the police acted to reinforce normative gender by ensuring that dress was not deceptive. In 1972, teenagers Jerome Swigart and Frederick LaFitte, for example, were simply walking down the street wearing women's clothing in Sarasota, Florida, when they were picked up and later charged with “appearing in the dress of another person not belonging to the same sex.” Footnote 70 When defendants challenged these sorts of arrests, police and prosecutors often attempted to justify their actions by referencing their fear of men using women's bathrooms. Footnote 71 The Houston chief of police told a reporter, “We have a lot of people here who would like to dress in women's clothes and ‘tippie toe’ in and out of women's restrooms,” when asked why he was enforcing the city's anti-cross-dressing ordinance in 1972. Footnote 72

Penalties for cross-dressing varied considerably, including fines of $1 to $100 or more, and nights or months in jail. Footnote 73 Even when the legal consequences were relatively minor, humiliation and abuse by police could render the impact of an arrest quite terrible. In the early 1960s, a traveling salesman and transvestite was arrested while “dressed” in an unfamiliar town after a solo dinner in a local restaurant. After he changed into masculine clothing and spent the night in jail, the assistant chief of police demanded that he get “dressed” again, took gratuitous mug shots of him, and proceeded to “lead various men into the room and tell each one, ‘I'll give you fifty bucks if you'll mount her.’” As he wrote in his account of the ordeal, he had "tears streaming down my face.” Footnote 74 In 1971, a trans woman arrested in Dallas recounted that after her arrest, the police “took my clothes and put me in a release tank with male prisoners for one hour with nothing on except a girdle and shoes.” To underscore why this abuse was so traumatic, she added, “I have a quite well-developed bust now after nine months of shots,” a reference to hormone treatment. Footnote 75 Two years later, two trans women arrested for violating Chicago's anti-cross-dressing ordinance were forced to strip to their underwear for photographs at the police station; at trial, the officers explained that they wanted to “prove” that they were both men. Footnote 76 In these kinds of first-person accounts, gender outlaws regularly describe police officers teasing, humiliating, and degrading them.

A particularly horrific string of police abuses against a trans person named Linda Sue Jackson ultimately led to criminal convictions against four deputy sheriffs in Hot Springs County, Arkansas. Officers arrested Jackson, who worked as an Avon salesperson, several times over the course of 1977. On the occasion of one arrest, they were “forced to appear naked” in the Malvern City Jail, and, according to eyewitnesses, police then taunted and beat them. Footnote 77 After a subsequent arrest, officers drove to a remote location where Jackson was beaten “with nightsticks and flashlights, had turpentine poured into [their] anus, and was set upon by two Doberman pinschers. One of the officers then poured alcohol on [Jackson's] wounds and asked to be fellated.” Footnote 78 According to the report in Drag magazine, “a physician at the trial described [Jackson] as the most severely beaten patient he had ever treated.” Footnote 79 Although the language of anti-cross-dressing ordinances may make them appear as relatively harmless misdemeanor offenses, these arrests made gender outlaws vulnerable to police abuse.

One of the most striking features of the reported cases is that there are no detectable trans men, drag kings, or transvestite women. Footnote 80 Most of the defendants were drag queens, male transvestites, and trans women, with some occasional “hippies” and gender-bending revelers, both gay and straight men. Footnote 81 This archive reflects police priorities of the period, which focused on sexual deviance among people the police perceived to be men. Race is another troubling elision in the archive. Footnote 82 None of the print sources mentions the race of any of the defendants, and oral history interviews can only provide an outsider's impression. These significant limitations should not be taken to reflect the nature of anti-cross-dressing enforcement in general but do tell us which defendants were most likely to have the time, money, and access to lawyers necessary to challenge their convictions.

During the 1960s and 1970s, two concurrent developments in the social experience and scientific study of gender non-conformity transformed the way that gender outlaws understood themselves. Footnote 83 First, doctors and gender outlaws inaugurated a “taxonomic revolution” that reconfigured the relationships between sexuality, gender identity, and gender presentation in medicine and social life. Footnote 84 Sexologists had already begun to peel sexual object choice away from gender nonconformity, defining homosexuality by same-sex attraction and transvestism by cross-dressing. Footnote 85 At mid-century, they debated the place of transsexuals—people who sought medical interventions for sex change—in this schema. Footnote 86 Harry Benjamin developed the prevailing view that, unlike transvestites who wished to appear as the opposite sex, transsexuality reflected deeper cross-gender identification. Footnote 87 In order to access surgery in the Benjamin model, transsexuals were required to undergo a psychological evaluation and years of social transition, which included prescribed cross-dressing and hormones. Footnote 88 Although sexologists continued to debate terminology and acknowledged that many of their patients existed in the gray areas between the neat categories, their work generated stronger analytical distinctions between homosexuality, transvestism, and transsexuality. Footnote 89 Of course, shifts in elite discourses like medicine do not translate directly into social life, and many people we might now consider trans would refer to themselves as simply “gay.” Footnote 90

Gender outlaws also drove this process by developing new trans social networks and community knowledge about gender identities. Louise Lawrence collaborated directly with sexologists, sharing her trans experiences with researchers at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) throughout the 1940s and 1950s. Footnote 91 Lawrence became a mentor to Virginia Prince, who founded Transvestia magazine as well as a social club for fellow heterosexual transvestites in Los Angeles in 1960. Footnote 92 Throughout the 1960s, Prince and other contributors used the pages of Transvestia to define and police the boundaries of transvestite identity. Footnote 93 They understood gender identity to be separate from sexual orientation, dividing up transvestites into straight and gay categories and seeing both as different from transsexuals. Most of the contributors to Transvestia shared Prince's sense of themselves as heterosexual, middle-class, mostly white transvestites, or “TVs,” and disliked being confused with gay transvestites or “gay queens.” Footnote 94 More inclusive gender outlaws like the editors of Drag also contributed to the category work. Footnote 95

Emerging networks did much more than moderate border skirmishes at the sexual margins. They also created circuits for sharing information and building community. In the mid-1960s, Prince's social club blossomed into FPE. Footnote 96 From four initial chapters in Los Angeles, Chicago, Cleveland, and Madison, the group grew to twenty-five chapters by 1975. Footnote 97 In the relative safety of a member's living room, transvestites could dress how they liked while sharing beauty tips and relationship advice, as well as medical and legal knowledge. Prince frequently compared FPE to Alcoholics Anonymous as a place where “group commitment” could help transvestites “handle” their desires. Footnote 98

In San Francisco, smaller networks of transsexual activists and service groups also formed over the latter half of the 1960s. Trans women launched Conversion Our Goal (COG), the first known transsexual peer support and activist group, in response to police harassment in the Tenderloin district. Footnote 99 COG often referred trans people to the city's Center for Special Problems, where they could obtain unofficial ID cards indicating that they were under treatment for transsexualism. Footnote 100 The group found initial financial support from the Erickson Educational Foundation (EEF), a nonprofit founded and controlled by a wealthy trans man named Reed Erickson. Footnote 101 Through Erickson's continued investment and federal funding later in the decade, and with the leadership of trans women Louise Ergestrasse and Wendy Kohler, COG transformed into the Transexual Counseling Service, which connected trans people to medical and legal support while conducting its own educational outreach. Footnote 102

Trans people in New York and Los Angeles began to form their own political and service groups in 1970, having participated in the Stonewall uprising only to be effectively shut out of gay liberation organizations. Footnote 103 Street queens Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson organized Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, or STAR, to help street youth access food and shelter. Footnote 104 In Los Angeles, drag queen Angela K. Davis founded Transvestite/Transsexual Activist Organization (TAO), which drew greater connections to an international trans community through its publications Mirage and Moonshadow. Footnote 105 That same year, drag queen Lee Brewster and transvestite Bunny Eisenhower formed the Queens Liberation Front and began publishing the era's most thorough accounts of trans activism in Drag magazine. Footnote 106 Queens Liberation Front put legal change at the top of its agenda by prioritizing the “right to dress as we see fit” in its original prospectus. Footnote 107 By its own account, the group had some success pressuring authorities in New York to remove anti-cross-dressing provisions in permits for dances, catering, and cabarets. Footnote 108

Whether by accessing services, attending events, joining a club, or reading a magazine, gender outlaws in the late 1960s and early 1970s could link into a growing political network. Many of the organizations failed after only a few years of operation due to disagreements between leaders and lack of funding. But the period is marked by persistent efforts to bring legal issues for gender non-conformers into circulation. The small world of trans publications shared tips for managing an arrest, fictionalized accounts of cross-dressing prosecutions, and news items covering cross-dressing law enforcement and challenges to ordinances. Footnote 109 Transvestia canvassed readers for “any cases in which the courts have given any kind of verdicts favorable directly or indirectly to transvestism.” Footnote 110 A typical news item from Drag magazine in 1973 told readers that Toledo's anti-cross-dressing law had been found unconstitutional and would no longer pose a threat to drag attendees of the city's annual Halloween Ball. Footnote 111 Turnabout, a short-lived trans magazine out of Brooklyn, published a three-part series on transvestism and the law. Footnote 112 EEF also published pamphlets to educate trans people about their legal options. The 1971 edition of “Legal Aspects of Transexualism” included the names and addresses of three sympathetic attorneys and began its analysis with cross-dressing regulations. Footnote 113 Since many ordinances included an intent requirement, EEF recommended that trans readers write in for unofficial EEF identification cards, which would explain that cross-dressing was part of the treatment protocol.

The coverage consistently portrayed transvestites as a minority. Footnote 114 In the pages of Transvestia, Virginia Prince told readers that supporting John Miller “is definitely in the interests of all TVs” because they could be a part “of the first legal effort ever collectively made in the interest of TVs.” Footnote 115 Turnabout’s Siobhan Fredericks also described the case as one about transvestite rights, calling it “the ideal ‘test case’” for challenging New York's masquerade law. Footnote 116 Making rights claims as trans people did not necessarily translate into legal arguments based on trans identities, however. Prince was notorious for defining transvestism against homosexuality and transsexuality, and yet she articulated this expansive legal imagination. She suggested that challenges to cross-dressing regulation like Miller's would promote “freedom of expression in clothing” and “greater freedom for the male to express himself.” Footnote 117 Taken at face value, such arguments could benefit a broader range of gender outlaws than the group of transvestites Prince allowed to join FPE. Footnote 118

Trans organizations also contributed to a greater public understanding of trans legal problems. In San Francisco, Wendy Kohler led a pioneering day-long workshop on transsexual issues including doctors, policy experts, and service providers. Footnote 119 Throughout her extensive domestic travels, Virginia Prince made a point of attempting to dissuade local police officials from enforcing anti-cross-dressing laws. Footnote 120 During a visit to a bar for “gay queens” in Honolulu, Prince learned that trans women attempted to avoid arrest by pinning signs stating “I am a Boy” to their dresses. Footnote 121 She arranged a meeting with the local police in an attempt to explain transvestism so that they would “treat TVs with some understanding.” Footnote 122 On a visit to Los Angeles in 1966, she took a detour to San Diego to try to persuade the police department not to endorse a new anti-cross-dressing ordinance there. Footnote 123 EEF also tried to educate law enforcement by publishing “Information on Transexualism for Law Enforcement Officers.” Footnote 124 The booklet was organized in an accessible question and answer format, offering its take on quandaries like “what is a transsexual” and “isn't cross-dressing against the law?” Footnote 125

These combined efforts trickled into the legal profession, in part through EEF's financial support for articles on trans issues. Starting in 1968, Colorado attorney John P. Holloway wrote a series of articles entitled “Transexuals—Their Legal Sex,” “Transexuals: Legal Considerations,” and “Transsexuals—Some Further Legal Considerations,” which he had researched with cooperation from sexologists at Johns Hopkins University. Footnote 126 Holloway presented his findings at the EEF's second International Symposium on Gender Identity in Copenhagen. Footnote 127 Another attorney published an article on trans law in the Cornell Law Review, which EEF advertised on the first page of its winter 1971 newsletter. Footnote 128 By 1983, EEF's legal referral list had grown to thirty-eight names. Footnote 129

As trans organizing expanded alongside widespread challenges to police abuse in the mid-1960s, it might seem overdetermined that challenges to cross-dressing laws would also increase. But going to court opened a trans person to retaliation in their private and professional life. Transsexuals seeking surgical care faced a particular double-bind: to access surgery, doctors pressured them to “pass” as cisgender through social transition; but in order to mount a defense, they would have to make their gender history public. Footnote 130 In the words of trans theorist Sandy Stone, transsexuals were “programmed to disappear.” Footnote 131 Speaking in court about their gender identity did not exactly qualify.

Trans people took that risk. As criminal defendants, they were already in a defensive position relative to legal authority and may have felt that fighting the charges might improve a bad situation. Most of the reported cases began when a trans person was arrested for cross-dressing. Rather than suffer the punishment privately, these defendants decided to appear in court to raise constitutional objections to the legitimacy of cross-dressing regulations. For their part, defense lawyers groped for statutory interpretation and constitutional arguments amid significant legal change. In the 1960s, as state vagrancy laws came under pressure, it was not obvious whether arrests would be more vulnerable to legal attacks that characterized cross-dressing as harmless sartorial conduct or expression of a personal status.

In a series of cases including John Miller's defense, attorneys in New York tried to challenge Section 887(7) by arguing that it was unconstitutionally vague, exceeded the state's police power, and required criminal intent that ruled out application to cross-dressers. Footnote 132 Prosecutors retorted that the laws clearly prohibited androgynous dress. In opposition to John Miller's appeal, for example, the district attorney reinforced the popular notion that cross-dressing was essentially deceptive conduct. By “hiding in the guise of women,” he wrote, “transvestites necessarily frustrate minimum standards of societal order.” Footnote 133 Since conduct could be criminalized under the police power, Miller's challenge failed. Even judges who might find such readings excessive still believed that the law was intended to discourage “overt homosexuality” and “sexual aberration.” Footnote 134

As long as courts understood cross-dressing to be criminal conduct, it was difficult to convince them that the laws exceeded municipal power to regulate welfare. But in the late 1960s and early 1970s, lawyers convinced judges in state courts across the country that similar laws were, in fact, unconstitutional. These lawyers relied on the growing popularity of unisex fashions, the expanding protections for personal expression, and changes in the science of transsexuality to develop legal theories that the laws were void for vagueness, violated personal freedoms, and criminalized transsexual medical diagnoses.

Each of these strategies reflected a different understanding of the relationship between cross-dressing and personal identity. In the vagueness cases, lawyers often steered courts away from inquiries into the deeper meaning of their clients’ cross-dressing, instead folding the dressing practices of gender outlaws such as gay party-goers, drag queens, transvestites, and transsexuals into the broader trend toward unisex styles. By contrast, challenges rooted in the First and Fourteenth Amendments asserted something like a freedom to cross-dress as part of defendants’ right to choose their clothing, either as a form of protected expression or as a substantive due process right.

A final subset of cases raised arguments under the Eighth Amendment, framing trans identity as an “involuntary condition” that could not be criminalized. This theory drew judicial attention closest to defendants’ personal identities and gained sympathy in court by highlighting the double-bind facing transsexuals. Regardless of which strategy lawyers deployed, even in cases in which judges were not asked to adjudicate the defendant's gender identity, these challenges represented a crucial turning point in the legal legibility of trans people.

No single set of lawyers was responsible for the strategy, but the ACLU played an outsized role. Footnote 135 Regional ACLU chapters had supported local challenges going back at least as far as John Miller, whose attorneys secured an amicus brief from the civil rights juggernaut. Footnote 136 In 1973, attorneys in the national office founded the Sexual Privacy Project, which included cross-dressing challenges alongside challenges to laws banning sodomy, loitering, solicitation, and prostitution, as well as sex offender registration and cohabitation regulations. Footnote 137 Led by Marilyn Haft, the Project worked on three other challenges in St. Louis, Louisville, and Winston-Salem in its first year of operation. After the Sexual Privacy Project closed in 1977, the short-lived Transsexual Rights Committee of the Southern California ACLU took up similar work. Footnote 138 It advanced important changes for trans people in California and provided materials to attorneys challenging cross-dressing laws elsewhere. Footnote 139

The Supreme Court's landmark decision in Papachristou v. City of Jacksonville clarified the terms of debate by making it more difficult to criminalize conduct. The decision of 1972 invalidated Jacksonville's vagrancy ordinance on the grounds that it “fail[ed] to give a person of ordinary intelligence fair notice that his contemplated conduct is forbidden by the statute,” and made “criminal activities which by modern standards are normally innocent,” in violation of due process guarantees in the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. Footnote 140 The Court reined in police discretion by ruling that citizens must have fair notice of what conduct is considered illegal. Footnote 141

Papachristou rendered anti-cross-dressing ordinances newly vulnerable to vagueness challenges in the 1970s. In fact, it was the dispositive argument in half of the twenty-seven challenges recorded in legal reports and trans press between 1963 and 1986. The explosion of unisex clothing also made it much more difficult for police or judges to tell that a person's clothing was intended for men or for women. As a judge put the problem, “What distinguishes the male high-heeled shoe from the female? Is it the thickness of the heel or the sole, the design of the toe, the contour of the instep or just what?” Footnote 142 In an age of unisex clothing, how could an ordinary citizen determine whether their clothing would violate the law?

Over the previous decade, an array of social movements explicitly politicized self-presentation as part of their protest of the status quo: Male hippies and youth activists began to wear their hair long and adopt unisex fashions to protest the clean-cut political establishment behind the Vietnam War; Black Power activists encouraged African Americans to reject white standards of beauty by embracing natural hairstyles and African-inspired clothes; feminists wore pants as a sign of gender equality; and gay male liberationists embraced the “Peacock Revolution” in menswear, with its emphasis on bright colors and accessories. Footnote 143 Cross-dressing among men had long been associated with male effeminacy and homosexuality, connections that raised fears about the “homosexual conspiracy” behind unisex styles when they first emerged. Footnote 144 These styles were quickly shorn of their countercultural roots. By the 1970s, “long hairstyles on men, pants on women, and unisex fashions were no longer restricted to baby-boomer youths or social movement activists,” as they made their way into the cultural mainstream. Footnote 145

Lawyers in several cases solicited testimony at trial to underscore the difficulty of enforcing cross-dressing bans in light of unisex clothing. In 1971, the ACLU of Florida teamed up with the Gay Activists Alliance of Miami and the National Coalition of Gay Organizations to argue that Miami Beach's anti-drag and anti-cross-dressing ordinances were unconstitutionally vague. The lawyers called the chief of police to testify and showed him “some 15 items of unisex apparel obtained from a local clothing store and asked if a man wearing them would be subject to arrest for appearing in clothing inappropriate to his sex.” He responded that “it would depend on the person and the circumstances.” Footnote 146

In Detroit, two courts called fashion writers from the Detroit Free Press to testify about the difficulty in separating men's from women's clothing. Footnote 147 One writer explained that “the distinction between male and female clothing has blurred tremendously, and . . . clothes have become sexless.” Footnote 148 In 1975, the Supreme Court of Ohio similarly relied on the unisex clothing trend when it faced a challenge to the cross-dressing ordinance in Columbus. “Modes of dress for both men and women are historically subject to change in fashion,” wrote Chief Justice C. William O'Neill. “At the present time, clothing is sold for both sexes which is so similar in appearance that ‘a person of ordinary intelligence’ might not be able to identify it as male or female dress. In addition, it is not uncommon today for individuals to purposefully, but innocently, wear apparel which is intended for wear by those of the opposite sex.” Footnote 149 The court unanimously ruled the ordinance void for vagueness. Footnote 150

By referencing the ubiquity of unisex styles, lawyers implied that the dressing practices of their clients were not unique to sexual or gender subcultures but benign parts of a larger shift. The approach worked to the advantage of the defendants in two of the cases discussed. Footnote 151 These arguments also enabled lawyers to skirt questions about their client's intent or identity while still winning the case. Judges invalidated old laws without having to adjudicate the sex or gender of defendants or understand much of anything about how gender outlaws identified.

A separate line of Supreme Court cases opened another avenue for challenging cross-dressing regulation. In the 1960s, constitutional protections for free expression expanded to include new recognition of the right to control one's personal appearance. Some lawyers seized on these developments to argue that cross-dressing was a component of personal expression for their clients. In the process, they shifted the legal meaning of cross-dressing away from associations with gender fraud and stigmatized homosexuality, carving out some protections for gender non-conformity on its own terms. Footnote 152

In a string of cases during the late 1960s, the Supreme Court was forced to grapple with the extent of First Amendment protections for various forms of protest against the Vietnam War. In 1968, the Court held that burning draft cards did not merit constitutional protection, but the following year, it ruled that wearing black armbands at school was protected symbolic conduct in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District. Footnote 153 An important element of that case was the Court's assertion that the armbands were protected even though other students and school staff found it distasteful. In the 1974 case Spence v. Washington, the Court similarly found that a student's right to fly the American flag upside down outside his dorm window was protected by the First Amendment. Footnote 154 Where previous decisions defined the limits of “pure speech,” these cases expanded First Amendment protections to expressive forms of symbolic conduct, including some elements of personal appearance.

Federal courts in the early 1970s were also inundated with cases brought by public employees, prisoners, members of the military, and public school students against male dress and grooming codes. Their victories helped expand constitutional protection for personal appearance under a different set of constitutional arguments emanating from the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Footnote 155 These “long hair cases” culminated in Kelley v. Johnson, which reached the Supreme Court in 1976. Footnote 156 The case concerned a patrolman's challenge to his department's requirement that male police officers be clean-shaven and keep their hair short. While the officer lost his case, the Court limited its decision to the specific circumstances of policemen as public employees, leading observers (and subsequent circuit courts) to conclude that the Court recognized “some sort of ‘liberty’ interest within the Fourteenth Amendment in matters of personal appearance” for the first time. Footnote 157 Together, the Tinker and Kelley decisions suggested that personal appearance was constitutionally protected to some extent, although the precise contours remained unclear.

Attorneys for Martin Hirshhorn anticipated these developments by several years. Hirshhorn, who also used the name Sandy Lorin, was a licensed hairdresser who had been wearing exclusively women's clothes for three years when they were arrested in 1965 for cross-dressing. Footnote 158 ACLU lawyers came to Hirshhorn's aid and petitioned the Supreme Court to invalidate the law for abridging the “right to dress as one pleases” under the substantive due process guarantee of the Fourteenth Amendment. Footnote 159 That articulation of the right at issue made it possible, at least in theory, for the Court to agree without knowing why Hirshhorn had been wearing women's clothes when they were arrested.

As a result, Hirshhorn's lawyers did not need to take a position on whether cross-dressing was a conduct or a status. Footnote 160 In fact, they referred to it both ways in a single paragraph, arguing that “to criminally punish for conduct completely dissociated from any criminal intent and totally unrelated to any criminal act cannot be defended on any grounds. The State, in effect, is arbitrarily making mere status a criminal offense.” Footnote 161 They argued that since Hirshhorn “is a transvestite,” and transvestism is not itself illegal, Hirshhorn was being punished simply for the act of wearing women's clothes. Footnote 162 But they also explained that for Hirshhorn, cross-dressing “defines [their] identity,” which constitutes a “unity and persistence of personality.” Footnote 163 Rather than challenge the notion of gender fraud, they argued that Hirshhorn would be “concealing [their] identity only if [they] wore men's clothing.” In other words, Hirshhorn avoided gender fraud by cross-dressing. Footnote 164

It might have been anathema in sexology to see transvestism as both conduct and status, but in this situation, Hirshhorn's lawyers improved their prospects by declining to pick a side. They appeared to be aware of the growing movement to define a discrete transsexual status since they cited a front-page headline from The New York Times in 1966, declaring “A Changing of Sex by Surgery Begun at Johns Hopkins” as evidence that “modern surgical innovations would also seem to make meaningless the sanctions of this statute.” But, as Risa Goluboff has remarked, the attorneys fell short of arguing that transgender people constituted a minority deserving constitutional protection. Footnote 165 The form of their legal argument might hold part of the explanation why—they may have decided that it was too risky to introduce judges to a developing taxonomic field when any definition of cross-dressing that linked it to sartorial freedom would do. We'll never know what the Court would have made of that argument, since the Supreme Court declined to hear Hirshhorn's case in 1967, as it had declined to hear John Miller's case a few years prior.

These arguments appeared again in the early 1970s after the Supreme Court had developed the speech and due process principles of free expression in Tinker and Kelley. From the start of the five-year battle to topple Chicago's anti-cross-dressing ordinance, freedom of personal appearance arguments were powerful tools for defendants and their lawyers. The opening salvo against the ordinance came from the courtroom of Circuit Court Judge Jack Sperling in a case concerning the arrest of four gender outlaws between the ages of seventeen and twenty. Melinda, Mona, Tanya, and Tammie had gone to the police one evening in 1973 to report that they had been beaten up at a local tavern after one of them had used the ladies’ room, only to be arrested inside the police station for cross-dressing. Footnote 166

Under “Public Morals” heading, Section 192-8 of the Chicago Code imposed a fine between $20 and $500 on “any person who shall appear in a public place in a dress not belonging to his or her sex, with intent to conceal his or her sex.” Footnote 167 Noted civil rights lawyer Renee Hanover represented the young people for free. She argued that the ordinance violated due process, was unconstitutionally vague, and violated the defendants’ constitutionally protected freedom of personal appearance. Footnote 168 Assistant Corporation Counsel Arthur Mooradian defended the ordinance “because a transvestite ‘with intent to deceive’ could enter women's washrooms,” rob unsuspecting strangers, or trick potential romantic partners. Footnote 169 According to local press, Judge Sperling ruled the ordinance unconstitutional by basing “his decision on recent cases . . . declaring government dress codes unconstitutional” because people “have the right to present themselves physically to the world in the manner of their own individual choice.” Footnote 170 Within three days of the Sperling decision, Melinda Balderas was evicted from her apartment, Tanya Williams lost her job, and Mona Garcia's house was burned down. Footnote 171

In 1974, gender outlaws got another chance to challenge the Chicago law. The case began when two plainclothes officers arrested Wallace Wilson and Kim Kimberley as they left a breakfast restaurant in Chicago's bustling downtown Loop neighborhood. According to the police, Wilson was wearing a “black knee-length dress, a fur coat, nylon stockings and a black wig;” Kimberley “had a bouffant hair style and was wearing a pants suit, high-heeled shoes and cosmetic makeup.” Footnote 172 At the station, the officers forced Wilson and Kimberley to disrobe and photographed their genitals. Wilson and Kimberley decided to fight their arrest, asking the Legal Assistance Clinic at Northwestern University School of Law to represent them. Footnote 173 Thomas Geraghty, a recent graduate, and law students Wendy Metzler and Daniel Swartzman aggressively fought the arrests. Their legal argument was both broad and narrow: it was couched in capacious terms as constitutional protection for an individual's right to cross-dress but was fueled by the expressive importance of cross-dressing for these defendants as trans women. The strategy highlighted the stakes of the right at issue but defined the protected group as medicalized transsexuals.

At trial, Wilson and Kimberley explained that they wore women's clothing not with “intent to conceal” their sex but with intent to express it. Both Wilson and Kimberley testified that they were transsexuals and that dressing in women's clothing was part of their treatment in anticipation of surgery. Wilson told the court, “I feel more comfortable in the clothes I was arrested in because that is the way I like to dress. I consider myself a female, but I am a male.” Footnote 174 Wilson and Kimberley hoped to show the judge that their expressive conduct was following doctor's orders. The judge was unconvinced, however, ruling that the ordinance properly regulated “public conduct” and could be upheld since Wilson and Kimberley intended to “conceal the fact that they are males.” Footnote 175 He fined each of the defendants $100.

On appeal to the Illinois Supreme Court, the legal team tried a handful of constitutional arguments, hoping that one would stick. Footnote 176 The brief educated the court about the developing science of gender identity by attaching an appendix including medical research from Harry Benjamin and other leading sexologists, a publication of the Gender Identity Clinic at Johns Hopkins University, and EEF's “Information on Transsexuals for Law Enforcement Officers.” Footnote 177 Bringing medical definitions of transsexuality into the courtroom made it easier for the judge to see a contradiction between the standards of medical care for transsexuality that required cross-dressing and the city law that criminalized it.

In their substantive due process argument, the lawyers articulated an expansive view that the Constitution protects “the right to dress as one pleases.” For Wilson and Kimberley, that right was all the more important because they were trans women who were “psychologically compelled to engage in such expression through dress and hairstyle.” Footnote 178 They embedded a First Amendment claim in this larger argument by analogizing the right to expression in clothing to symbolic speech communicating that Wilson and Kimberley were women. Footnote 179 In other words, cross-dressing was not necessarily an attempt to conceal one's sex but could be a part of trans identity. Applying the rule of Tinker, Chicago could not suppress the idea conveyed by Wilson and Kimberley's dress, even if some members of the public did not like it.

The Supreme Court of Illinois held that the Chicago cross-dressing ordinance was unconstitutional as applied to transsexuals because it violated their substantive due process right to dress as they pleased. Footnote 180 Justice Moran's opinion leaned on medicine. He had conducted his own research on transsexuality and the law, and his decision cited three law review articles (not referenced in the defense's appendix) for the proposition that cross-dressing was a part of trans medical treatment. After striking out at trial and the appellate court, the decision was a major victory for transsexual rights. It meant that the law could no longer be used to arrest transsexuals for cross-dressing in the city and enshrined a positive portrayal in the state law reporter. Footnote 181

In another sense, however, the defense's arguments had worked too well. The lawyers wanted to underscore that the liberty interest in clothing had deep stakes for their clients, so they conveyed cross-dressing as primarily a part of medical treatment for transsexuals. This logic structured the decision, limiting its protections to cross-dressing motivated by transsexuality. In other words, legal legibility came at the price of a narrow trans legal subject. Footnote 182 It reinforced the idea that transsexual identity was determined by doctors and implicitly defined it against other gender outlaws. The opinion defended the liberty to choose one's clothes but limited the sorts of people who could access that freedom. Footnote 183

Lawyers pushed arguments of medical necessity even further in challenges to cross-dressing arrests under the Eighth Amendment's prohibition on cruel and unusual punishment. Where Wilson and Kimberley's lawyers had suggested that cross-dressing was a medical necessity for transsexuals, some lawyers used recent Eighth Amendment developments to argue that transvestism and transsexuality were involuntary statuses. In the 1962 case Robinson v. California, the Supreme Court overturned a California statute that made “the status of narcotic addiction a criminal offense.” Footnote 184 The Court reasoned that an illness like drug addiction was an involuntary status, not an act, and to criminalize something “which may be contracted innocently or involuntarily” ran afoul of the Eighth Amendment. Footnote 185 In a few cases, lawyers took advantage of the fact that “transvestism” and “transsexualism” could be medical diagnoses, arguing that they were involuntary conditions and thus could not be criminalized under the Robinson rule. Footnote 186 Indeed, as Risa Goluboff has shown, ACLU attorneys Osmond Fraenkel and Stephen Stein also raised this argument in Martin Hirshhorn's unsuccessful appeal to the Supreme Court in 1967. Footnote 187

As Hirshhorn's case wound its way toward the Supreme Court, the long history of medical interest in gender minorities was gaining new cultural salience and institutional legitimacy. With financial support from Reed Erickson, sexologists at Johns Hopkins University founded a Gender Identity Clinic in 1966 and began to accept patients for sex-affirming surgery. Footnote 188 Clinics at Northwestern University, Stanford University, and the University of Washington soon followed. Footnote 189 Each clinic had its own rubric for evaluating which patients to approve for surgery, but the broad outlines were the same: patients required psychological evaluation to determine that they had persistent “crossgender identification,” and they were required to live in their preferred gender for months or years, often taking sex hormones, under medical supervision. Footnote 190

Lawyers representing transsexual clients quickly realized that the developing medicine could bolster their claims and began to call medical experts to testify at trial. For example, Dr. Bryon Stimson, chairman of the Department of Psychiatry Transsexual Protocol Committee of the Ohio State University Hospital testified at the trial of Joseph Zanders in 1970. Stimson explained that he had been treating Zanders for a year and a half, using “psychiatric examinations” and “social and emotional testing” to determine that Zanders was “a true transsexual” and “a prime candidate for transsexual surgery.” Footnote 191 He also took care to differentiate between transsexuality, transvestism, and homosexuality.

Stimson's testimony was a major factor in convincing Franklin County Municipal Court Judge Jenkins that Zanders's arrest for cross-dressing should be thrown out. So too was an article in the American Journal of Psychotherapy by Harry Benjamin, from which the judge quoted extensively in his decision. “It is apparent from the medical authorities cited that the true transsexual suffers from a mental defect over which [she] has little practical control,” wrote Jenkins. Since criminal sanction could not flow from “a mental disease or mental defect,” Zanders could not be punished under the ordinance. The decision reflected the same intuition driving Eighth Amendment challenges to cross-dressing ordinances, a sense that there was something unsavory about criminalizing an involuntary medical status. Footnote 192

But this approach was a high-wire act, requiring that the doctors give supportive testimony and that judges were receptive to their message. Zanders learned how easily the strategy could backfire when she appeared before the Ohio Court of Appeals for the Tenth District in 1974. In the four years after her successful legal challenge, she had been arrested for cross-dressing in Columbus six more times. For this appeal, Zanders mounted the same defense as before, arguing that “as a transsexual [her] course of conduct was prescribed by the doctor as a course of treatment for a clearly defined medical problem,” and the arrests were therefore unconstitutional. Dr. Stimson also made a repeat appearance, but this time he portrayed the state of transsexual medicine as unreliable, testifying that there were cases of “reversible transsexualism” and that the field lacked a “standard diagnosis.” Footnote 193 The appellate court was particularly interested to hear from Dr. Stimson that Zanders had been inconsistent in seeking treatment for the past several years and had not undergone surgery. Footnote 194 They took this evidence as an indication that Zanders may not have been sincere in her description of herself as a transsexual, despite Simson's additional testimony that Zanders met the medical requirements for surgery but simply could not afford the $30,000 price tag. Footnote 195 Simson's testimony cast doubt on Zanders's claims to medical necessity, and she lost all six appeals.

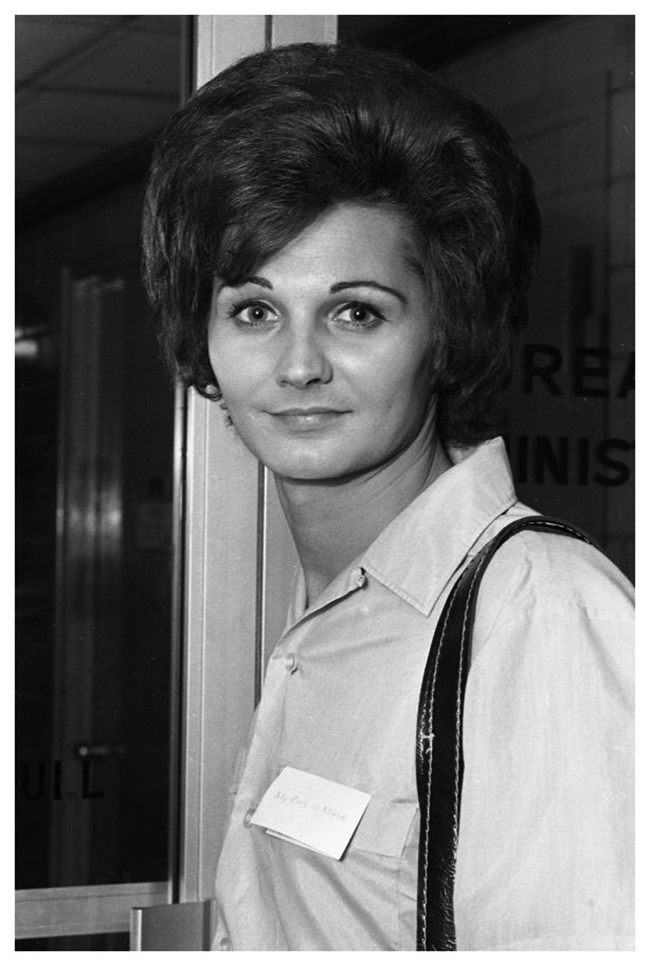

That same year, the ACLU made its third attempt to get the constitutionality of cross-dressing bans before the Supreme Court, this time pushing an Eighth Amendment strategy. Footnote 196 The client, a trans woman named Toni Rochelle Mayes, had socially transitioned in 1971, wearing women's clothing and taking estrogen as part of her treatment. Footnote 197 She asked the city council and, later, the police department if they would issue ID cards to gender outlaws that they could show to police officers to avoid arrest for violating the Houston ban on dress “of the opposite sex.” Footnote 198 Instead, the city council revised the ordinance to impose a penalty only if a Houstonian cross-dressed “with the intent to disguise his or her true sex as that of the opposite sex,” apparently hoping the change would make the law less vulnerable to legal challenge. Footnote 199 In order to avoid the appearance of using women's clothing as a disguise, Mayes started to wear a sign which read “my body is male” (Figure 2). Footnote 200

Figure 1. Cover cartoon in Femme Mirror, a transvestite magazine published by Tri-Sigma. Source. Femme Mirror, October 1978, cover.

Figure 2. Toni Mayes wearing a sign that reads “My body is male.” Toni Mayes portrait courtesy of Houston LGBT History Collection, JD Doyle Archive. Available at https://www.houstonlgbthistory.org/Houston80s/Misc/Cross%20Dressing/Mayes/Toni%20Mayes-1972.jpg.

The police department was unrelenting, using the ordinance to arrest Mayes eight times over a three-year period. On one occasion, she was put in a men's jail for nine hours, later telling the press, “I felt terrible. . . . I had my wig torn off and there were a lot of remarks I didn't care for.” Footnote 201 She reported that she'd spent “$1,000 in legal fees and bonds since I've been taking the hormones” and that she was “immediately recognized everywhere, can't get a job, and ha[d] no income.” Footnote 202 She decided to challenge the constitutionality of the ordinance to help protect other trans people from the same experience, recognizing that the publicity from a lawsuit could help educate the public. Footnote 203

Throughout her legal battle, Mayes and her lawyers hewed closely to the medical model of transsexuality. At trial, they called her doctor, a reproductive endocrinologist, to testify that she was transsexual and describe her physicality and mental state. Footnote 204 The defense team emphasized the fact that Mayes's cross-dressing was part of a larger plan to pursue sex reassignment surgery. Mayes herself testified that she “was a woman and therefore dressed like one,” and in their petition to the Supreme Court, her attorneys added that “an essential part of petitioner's status as a transsexual is the compulsion to wear female clothing.” Footnote 205

This evidence provided the necessary background to challenge Houston's ordinance under the Eighth Amendment. Five years after the Robinson decision, the Supreme Court seemed to backtrack on its holding. In Powell v. Texas, it ruled that Texas could impose criminal penalties for public intoxication because alcoholism was not clearly an involuntary status, and, in any case, the law concerned the public expression of that condition. Footnote 206 Marilyn Haft of the ACLU's newly formed Sexual Privacy Project saw the Mayes case as an opportunity for the Court to chart a course between Robinson and Powell. She argued that the Houston ordinance punished Mayes for her “status as a transsexual,” even though “the appearance in public of a transsexual in the clothing of the opposite sex is the passive and essentially involuntary expression of a status and does not harm others.” Footnote 207 She urged the Court to hold that the Eighth Amendment “prohibits punishment of public expression of a status when an essential and substantially involuntary ingredient of the status is to harmlessly act out and express that status in public.” Footnote 208 Quoting a concurrence from Robinson, Haft wrote, “we would forget the teachings of the Eighth Amendment if we allowed sickness to be made a crime and permitted sick people to be punished for being sick.” Footnote 209 But the Supreme Court would not hear the case, leaving Houston's ordinance in effect.

These cases were firmly grounded in a coherent sense of transsexual identity. They told courts that transsexual people were a minority group whose status could not be criminalized. Robinson looked like an attractive constitutional hook for a fledgling movement, but lawyers still took a risk in pursuing it, since it required trans people to ask their doctors to help them prove that their identities were legitimate. In structure, if not substance, these claims most resemble contemporaneous claims for gay and lesbian rights based on a consolidated sense of gay identity. The arguments tried to open an aperture in the Constitution just big enough for transsexual people under medical treatment to walk through, leaving other gender outlaws outside.

When trans defendants challenged their arrests as infringements on their right to dress as they pleased, or as cruel and unusual punishment, they steered state and municipal courts toward definitions of gender identity from political activism and sexology. Their challenges as criminal defendants helped courts understand the harms of anti-cross-dressing enforcement to trans legal subjects. In the 1980s, trans litigants built on this foundation through civil suits in federal court. Stuck between medical treatment regimes and law enforcement, these litigants made affirmative demands on state power.

For example, a group of seven trans women anonymously brought a civil lawsuit against the city of Houston in 1980. Footnote 211 On the case caption, they appeared as Jane Does to protect themselves from harassment, preserve their privacy, and stave off “prosecution resulting from this action.” Footnote 212 Many of the women had been arrested for cross-dressing in the past, and, if their lawsuit failed, they could become targets. Just ask Toni Mayes, who left the courtroom in her case only to be arrested again on the courthouse steps.

The plaintiffs went on the offensive, demanding that the court invalidate the ordinance and enjoin the police from enforcing it. When the district court ruled in their favor, it relied on the rationale from Chicago v. Wilson. Footnote 213 The opinion spent more time explaining transsexuality as a diagnostic category, differentiating it from homosexuality and transvestism, and elaborating on the “passing” requirement before surgery could be pursued, than it did on the legal content of the case. When it got there, the decision quoted a full paragraph from Chicago v. Wilson and held that the Houston ordinance was an unconstitutional intrusion on the substantive due process right to control one's personal appearance. It reasoned that for transsexual people, cross-dressing was “medically necessary.” Footnote 214

Like Chicago v. Wilson, the holding only extended to “individuals undergoing psychiatric therapy in preparation for sex-reassignment surgery.” Footnote 215 From the standpoint of all gender outlaws, it was a partial victory. The trans legal subject was limited to transsexual persons seeking medical care under a doctor's supervision, but the ruling also added to activist pressure on the ordinance, which the city council fully repealed four months later. Footnote 216 For transsexual Houstonians who had been harassed and prosecuted, the case was a watershed. The plaintiffs had proven that legal authority could recognize trans people as legible subjects, and some trans people could come out of criminal defense and play offense for trans rights.

The narrow frame of the trans legal subject shaped attorneys’ strategic imagination. In 1984, the ACLU of Eastern Missouri constructed a lawsuit to challenge prohibitions on cross-dressing and “lewd and lascivious conduct” in St. Louis's vagrancy ordinance. Footnote 217 The suit represented one trans woman who had been arrested under the anti-cross-dressing provision and one drag queen who had been arrested with other “female impersonators” in a gay bar raid. The lawyers understood transsexuals, transvestites, and homosexuals to be analytically distinct and also recognized that the ordinance targeted them all. Footnote 218 They asked the court to strike down the ordinance and sought $25,000 in damages under a federal anti-discrimination statute. Footnote 219 The case reached the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit, which agreed that both clauses were unconstitutionally void for vagueness. Footnote 220 Rather than seek constitutional protection for non-conforming dress in general, lawyers framed the case as a coalition between gay and trans people to tackle the entire ordinance. Gender outlaws and their lawyers had brought the taxonomic revolution to court, separating gender non-conformity from sexual orientation, and they had won. Legal defense of gender outlaws became a transgender legal movement.

By the mid-1980s, gender outlaws had succeeded in convincing courts across the country to throw out their cross-dressing arrests, and sometimes, their cross-dressing bans. Footnote 221 Lawyers and their clients found protections for gender outlaws in the Constitution, convincing courts all over the country that cross-dressing did not have to be a crime; it could be a benign fashion choice, an element of personal expression, or a medical treatment. In the process, they made strategic choices about when trans identities should be visible or obscured and negotiated the tension in winning cases for transsexual people in ways that other gender outlaws could not replicate. Out of the crucible of cross-dressing decriminalization emerged a viable—and yet limited—trans legal subject.

In retrospect, John Miller appears as a paradigmatic litigant in the emerging transgender legal movement. He identified as a transvestite within a national community that fiercely defended the boundaries between gender identity, sexual orientation, and gender presentation. With community financial support, he hired a lawyer to challenge New York's anti-masquerade law on vagueness grounds. And when he needed help with his appeal, he enlisted the New York Civil Liberties Union to write an amicus brief on his behalf.

How different was this, really, from the gay and lesbian legal movement emerging at the same time? Several elements of Miller's story look familiar. Certainly, the ACLU was a major institutional support in the 1960s, including its representation of homophile activists who were arrested for cross-dressing. Footnote 222 Evidence of gender non-conformity was often used to prosecute gay bars and patrons. Many early gay civil rights cases also argued that anti-gay laws were void for vagueness or asserted First and Fourteenth Amendment rights for gay people to freely assemble and receive due process. Footnote 223 It's also true that before (and during) the taxonomic revolution, sexual orientation and gender identity were so deeply entangled that it makes little sense to separate queer and trans social history.