150 years of art: some notable alums

It’s impossible to choose ten artists to represent the breadth and depth of the School of Art’s alumni. But we gave it a shot anyway.

Nov/Dec 2019

Yale University Art Gallery

Mary Foote ’06BFA (1872–1968), who took courses at the School of Fine Arts from 1890 to 1897, fit the profile of many early students: a young woman from a socially prominent Connecticut family. But she was more successful as an artist than most. She continued her studies in Paris for four years after leaving Yale, then set up a studio in New York in 1901. (Like many of the early art students, she was awarded her BFA after her time at Yale.) She made her name as a portraitist, producing likenesses of such prominent New Yorkers as suffragist Carrie Chapman Catt, sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, and arts patron Mabel Dodge Luhan (shown here), who became a close friend. Foote underwent psychoanalysis in the 1920s and went to Zurich to be a patient of Carl Jung; she ended up spending most of the rest of her life there, documenting and editing the proceedings of Jung’s celebrated seminars. She gave up painting on Jung’s advice. She returned to Connecticut in 1958 and died in 1968. View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

Mary Foote ’06BFA (1872–1968), who took courses at the School of Fine Arts from 1890 to 1897, fit the profile of many early students: a young woman from a socially prominent Connecticut family. But she was more successful as an artist than most. She continued her studies in Paris for four years after leaving Yale, then set up a studio in New York in 1901. (Like many of the early art students, she was awarded her BFA after her time at Yale.) She made her name as a portraitist, producing likenesses of such prominent New Yorkers as suffragist Carrie Chapman Catt, sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, and arts patron Mabel Dodge Luhan (shown here), who became a close friend. Foote underwent psychoanalysis in the 1920s and went to Zurich to be a patient of Carl Jung; she ended up spending most of the rest of her life there, documenting and editing the proceedings of Jung’s celebrated seminars. She gave up painting on Jung’s advice. She returned to Connecticut in 1958 and died in 1968. View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

Lois Conner ’81MFA (b. 1951) is one of the most prominent photographers to emerge from the School of Art since the program in photography was introduced in the 1970s. Conner found a favorite recurring subject while taking an art history course at Yale on Ming landscape paintings. It was as she was puzzling over otherworldly scenes of the Li River, she says, that “I asked my professor, why did they make up that kind of landscape? And he said, ‘That place really exists.’” In 1984, she was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship to see and photograph China for herself. She has returned every year to document natural landscapes (like the 1985 image shown here of Hangzhou), traditional scenes, and modern urbanism. Other Conner subjects include the American West and Native American life. Her equipment of choice for much of her work: an antique large-format (7 by 17 inches) banquet camera, so called because it was used in the early twentieth century to photograph large groups in formal settings. Conner directed Yale’s undergraduate photography program from 1991 to 2000 and also taught graduate students. View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

Lois Conner ’81MFA (b. 1951) is one of the most prominent photographers to emerge from the School of Art since the program in photography was introduced in the 1970s. Conner found a favorite recurring subject while taking an art history course at Yale on Ming landscape paintings. It was as she was puzzling over otherworldly scenes of the Li River, she says, that “I asked my professor, why did they make up that kind of landscape? And he said, ‘That place really exists.’” In 1984, she was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship to see and photograph China for herself. She has returned every year to document natural landscapes (like the 1985 image shown here of Hangzhou), traditional scenes, and modern urbanism. Other Conner subjects include the American West and Native American life. Her equipment of choice for much of her work: an antique large-format (7 by 17 inches) banquet camera, so called because it was used in the early twentieth century to photograph large groups in formal settings. Conner directed Yale’s undergraduate photography program from 1991 to 2000 and also taught graduate students. View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

Another Lois Conner image: a store window in Paris from 1979. View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

Another Lois Conner image: a store window in Paris from 1979. View full image

Fred W. McDarrah/Getty Images

“Art and work and art and life are very connected and my whole life has been absurd,” sculptor Eva Hesse ’59BFA (1936–1970—shown here with her sculpture “Repetition Nineteen” in 1968) once said. “There isn’t a thing in my life that has happened that hasn’t been extreme—personal health, family, economic situations.” Hesse’s life of extremes began with her Jewish family’s escape from Nazi Germany when she was three and ended with her death from a brain tumor at 34. She studied at Cooper Union before coming to Yale as a painting student. After graduating, she moved into sculpture, combining the minimalist sensibilities of colleagues like Donald Judd and Sol LeWitt with an eccentric palette of materials, such as latex, polyester, and fiberglass. Her greatest recognition came after her death, beginning with a 1972 Guggenheim Museum retrospective. View full image

Fred W. McDarrah/Getty Images

“Art and work and art and life are very connected and my whole life has been absurd,” sculptor Eva Hesse ’59BFA (1936–1970—shown here with her sculpture “Repetition Nineteen” in 1968) once said. “There isn’t a thing in my life that has happened that hasn’t been extreme—personal health, family, economic situations.” Hesse’s life of extremes began with her Jewish family’s escape from Nazi Germany when she was three and ended with her death from a brain tumor at 34. She studied at Cooper Union before coming to Yale as a painting student. After graduating, she moved into sculpture, combining the minimalist sensibilities of colleagues like Donald Judd and Sol LeWitt with an eccentric palette of materials, such as latex, polyester, and fiberglass. Her greatest recognition came after her death, beginning with a 1972 Guggenheim Museum retrospective. View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

An untitled Eva Hesse work of 1967 includes wood shavings and rubber tubing. View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

An untitled Eva Hesse work of 1967 includes wood shavings and rubber tubing. View full image

Chermayeff and Geismar and Haviv/Courtesy Tom Geismar

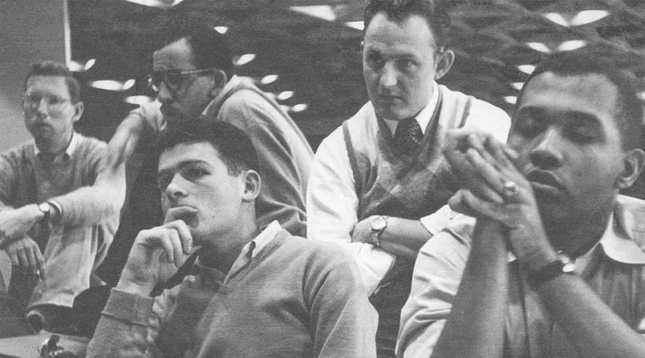

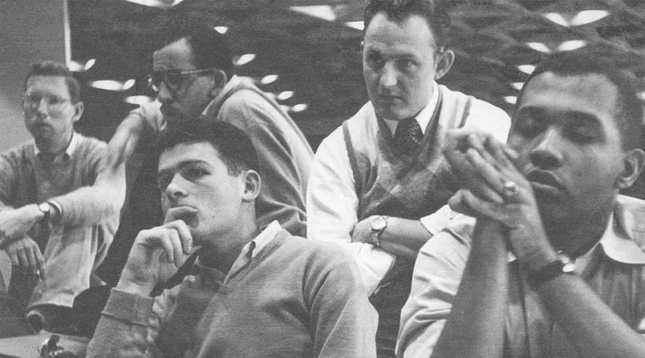

The art school’s graphic design program, launched in 1950, has graduated scores of designers of publications, corporate identities, film titles, and more. Two of the best known are Ivan Chermayeff ’55BFA (1932–2017) and Tom Geismar ’55BFA (b. 1932), who teamed up to start their own studio in 1957 and produced some of the world’s most recognized logos. (In this photo are Geismar--with hand on chin--and Chermayeff--in sweater vest—-as Yale students.) It’s hard to walk down an American street or turn on the TV without seeing their work for clients like PBS, NBC, Xerox, or National Geographic. Chermayeff died in 2017. Geismar continues with the firm, now called Chermayeff & Geismar & Haviv. View full image

Chermayeff and Geismar and Haviv/Courtesy Tom Geismar

The art school’s graphic design program, launched in 1950, has graduated scores of designers of publications, corporate identities, film titles, and more. Two of the best known are Ivan Chermayeff ’55BFA (1932–2017) and Tom Geismar ’55BFA (b. 1932), who teamed up to start their own studio in 1957 and produced some of the world’s most recognized logos. (In this photo are Geismar--with hand on chin--and Chermayeff--in sweater vest—-as Yale students.) It’s hard to walk down an American street or turn on the TV without seeing their work for clients like PBS, NBC, Xerox, or National Geographic. Chermayeff died in 2017. Geismar continues with the firm, now called Chermayeff & Geismar & Haviv. View full image

Chermayeff and Geismar and Haviv/Courtesy Tom Geismar

Tom Geismar devised an enduring logo for Mobil in 1964. View full image

Chermayeff and Geismar and Haviv/Courtesy Tom Geismar

Tom Geismar devised an enduring logo for Mobil in 1964. View full image

Chermayeff and Geismar and Haviv/Courtesy Tom Geismar

Chermayeff and Geismar’s logo for Chase Manhattan Bank. View full image

Chermayeff and Geismar and Haviv/Courtesy Tom Geismar

Chermayeff and Geismar’s logo for Chase Manhattan Bank. View full image

Chermayeff and Geismar and Haviv/Courtesy Tom Geismar

Ivan Chermayeff created the big 9 in front of 9 West 57th in Manhattan. View full image

Chermayeff and Geismar and Haviv/Courtesy Tom Geismar

Ivan Chermayeff created the big 9 in front of 9 West 57th in Manhattan. View full image

Thos Robinson/Getty Images

California native Richard Serra ’64MFA (b. 1938) got a degree in English before coming east to study painting at Yale. But his employment in steel mills had a major impact on his later work. Though his early sculptures used unconventional materials like neon, fiberglass, and rubber, he would find his greatest fame with works made from curving sheets of pre- oxidized steel, many of them site-specific works. Perhaps the best known of these, “Tilted Arc,” was the subject of controversy and legal battles in the 1980s when it was installed in a public plaza in Manhattan. It was eventually removed. In 1990, he created a sculpture called “Stacks” for the sculpture hall in Yale’s Old Art Gallery; it was later moved to the gallery’s sunken courtyard. Shown here at a 2007 MoMA retrospective is Serra’s “Band” (2006), an undulating 183-ton, 70-foot-long wall. View full image

Thos Robinson/Getty Images

California native Richard Serra ’64MFA (b. 1938) got a degree in English before coming east to study painting at Yale. But his employment in steel mills had a major impact on his later work. Though his early sculptures used unconventional materials like neon, fiberglass, and rubber, he would find his greatest fame with works made from curving sheets of pre- oxidized steel, many of them site-specific works. Perhaps the best known of these, “Tilted Arc,” was the subject of controversy and legal battles in the 1980s when it was installed in a public plaza in Manhattan. It was eventually removed. In 1990, he created a sculpture called “Stacks” for the sculpture hall in Yale’s Old Art Gallery; it was later moved to the gallery’s sunken courtyard. Shown here at a 2007 MoMA retrospective is Serra’s “Band” (2006), an undulating 183-ton, 70-foot-long wall. View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

“I began, and still do begin, with a love for color,” Jessica Stockholder ’85MFA (b. 1959) writes on her website, and one thing common to both her discrete sculptures and her large-scale installations is a riotous splash of bright color. Stockholder uses found objects in her assemblages, sometimes taking advantage of their existing color, sometimes adding paint (as in the untitled 1994 work shown here). The New York Times once wrote that her site-specific sculptures and installations “challenge boundaries, blurring the distinction among painting, sculpture, and environment, and even breaching gallery walls by extending beyond windows and doors.” Stockholder has also spent much of her career teaching: at Yale she was the director of graduate studies in sculpture from 1999 to 2011, and she is now the chair of the department of visual arts at the University of Chicago. View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

“I began, and still do begin, with a love for color,” Jessica Stockholder ’85MFA (b. 1959) writes on her website, and one thing common to both her discrete sculptures and her large-scale installations is a riotous splash of bright color. Stockholder uses found objects in her assemblages, sometimes taking advantage of their existing color, sometimes adding paint (as in the untitled 1994 work shown here). The New York Times once wrote that her site-specific sculptures and installations “challenge boundaries, blurring the distinction among painting, sculpture, and environment, and even breaching gallery walls by extending beyond windows and doors.” Stockholder has also spent much of her career teaching: at Yale she was the director of graduate studies in sculpture from 1999 to 2011, and she is now the chair of the department of visual arts at the University of Chicago. View full image

Mitchell-Innes & Nash

A Stockholder installation at the Sprengel Museum in Hannover, Germany, in 2000. View full image

Mitchell-Innes & Nash

A Stockholder installation at the Sprengel Museum in Hannover, Germany, in 2000. View full image

Eric Schaal/The Life Images Collection via Getty Images

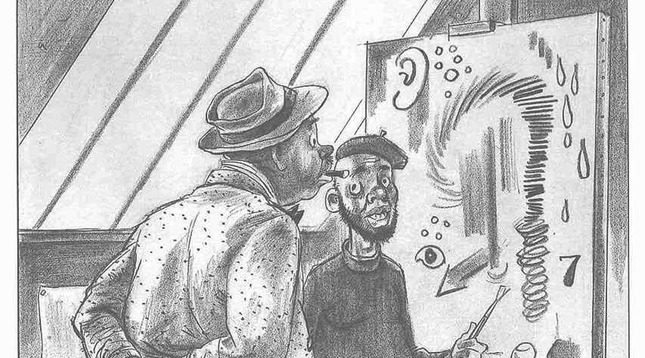

Like “Doonesbury creator” Garry Trudeau ’70, ’73MFA, Ollie Harrington ’40BFA (1912–1995--pictured at right) was a cartoonist before and after his time as a student at the School of Art. Langston Hughes called him “America’s greatest African American cartoonist.” Raised in the Bronx, Harrington created a comic strip about African American life for the Amsterdam News in 1935. First titled “Dark Laughter,” it was later renamed “Bootsie” for its central character. Harrington was a civil rights activist whose work was often political, and he left the United States for Paris in 1951 while under investigation by the FBI. In 1961 he sought political asylum in East Germany and spent the rest of his life there, continuing to work as a cartoonist. View full image

Eric Schaal/The Life Images Collection via Getty Images

Like “Doonesbury creator” Garry Trudeau ’70, ’73MFA, Ollie Harrington ’40BFA (1912–1995--pictured at right) was a cartoonist before and after his time as a student at the School of Art. Langston Hughes called him “America’s greatest African American cartoonist.” Raised in the Bronx, Harrington created a comic strip about African American life for the Amsterdam News in 1935. First titled “Dark Laughter,” it was later renamed “Bootsie” for its central character. Harrington was a civil rights activist whose work was often political, and he left the United States for Paris in 1951 while under investigation by the FBI. In 1961 he sought political asylum in East Germany and spent the rest of his life there, continuing to work as a cartoonist. View full image

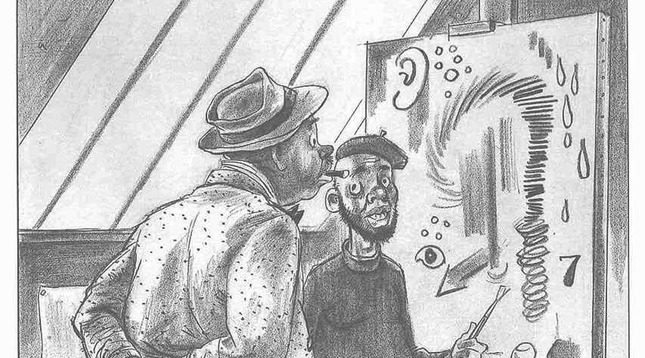

Collection of Dr. Walter O. Evans

One of Harrington’s “Bootsie” cartoons satirized abstract art. View full image

Collection of Dr. Walter O. Evans

One of Harrington’s “Bootsie” cartoons satirized abstract art. View full image

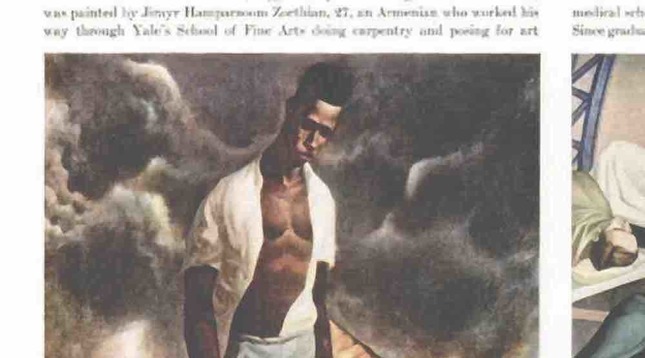

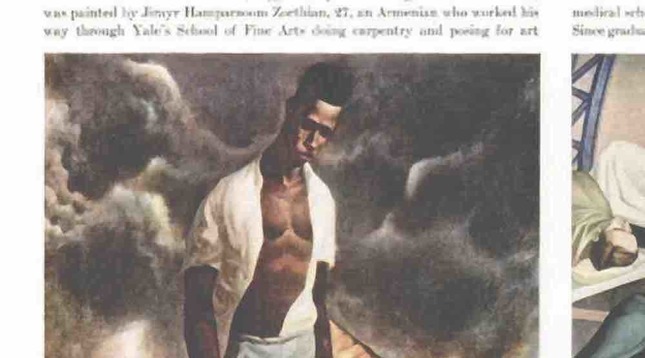

Life Magazine

One of Harrington’s student canvases, titled “Deep South,” was featured in a 1940 LIFE Magazine article about the school View full image

Life Magazine

One of Harrington’s student canvases, titled “Deep South,” was featured in a 1940 LIFE Magazine article about the school View full image

Timothy A. Clark/Getty Images

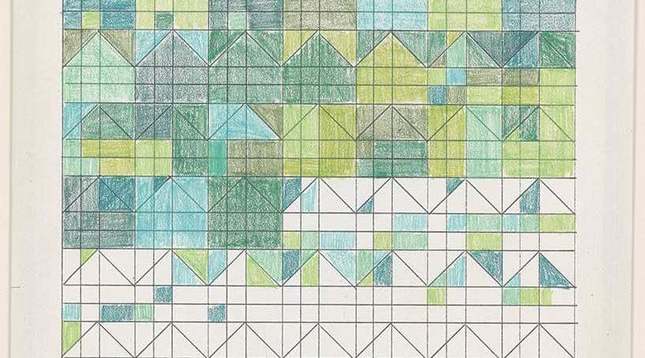

Jennifer Bartlett ’65MFA (b. 1941) came to Yale at an incredibly fertile time: her fellow students included Richard Serra, painter Chuck Close, and sculptor Jonathan Borofsky. “Yale was such a community,” she said in 2005. “All ambition, all the time.” Bartlett combined aspects of conceptual, abstract, and representational art: she painted and silkscreened images on one-foot- square steel panels and combined them in a grid to make murals. The murals sometimes reached monumental size, as in her 987-plate 1976 work “Rhapsody” (detail shown here). Bartlett’s thinking was summed up in the title of a 2013 retrospective: “History of the Universe.” View full image

Timothy A. Clark/Getty Images

Jennifer Bartlett ’65MFA (b. 1941) came to Yale at an incredibly fertile time: her fellow students included Richard Serra, painter Chuck Close, and sculptor Jonathan Borofsky. “Yale was such a community,” she said in 2005. “All ambition, all the time.” Bartlett combined aspects of conceptual, abstract, and representational art: she painted and silkscreened images on one-foot- square steel panels and combined them in a grid to make murals. The murals sometimes reached monumental size, as in her 987-plate 1976 work “Rhapsody” (detail shown here). Bartlett’s thinking was summed up in the title of a 2013 retrospective: “History of the Universe.” View full image

Locks Gallery

Another large-scale Jennifer Bartlett work: “Recitative” (2010). View full image

Locks Gallery

Another large-scale Jennifer Bartlett work: “Recitative” (2010). View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

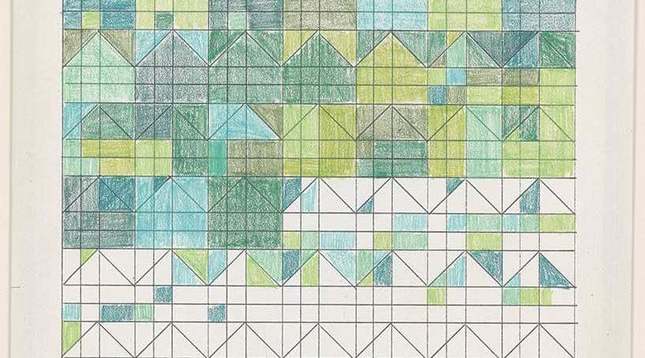

A more modest Jennifer Bartlett work--an untitled 1978 drawing--explores similar themes around order and systems. View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

A more modest Jennifer Bartlett work--an untitled 1978 drawing--explores similar themes around order and systems. View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

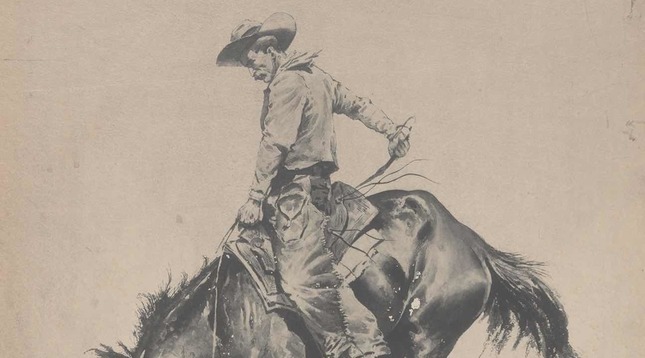

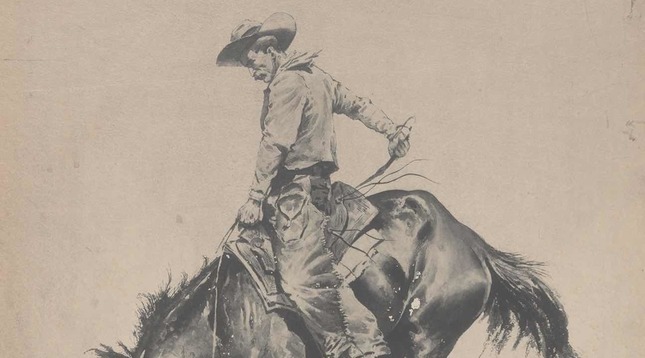

Painter, illustrator, and sculptor Frederic Remington ’00BFA (1861– 1909) was the only truly famous artist to come out of the School of Fine Arts in its first decades. Unlike most art students of his time at Yale (1878–79), Remington was welcomed into the extracurricular world of Yale College, playing on the football team and drawing cartoons for the Yale Courant. After his father died, he left school for the American West, discovering the subject that would bring him fame. His drawings of frontier life—-including works like Bronco Buster (shown here, 1895)—began appearing in magazines like Harper’s Weekly in 1882, and he soon became a chronicler of the masculine pursuits favored by his friend Theodore Roosevelt: cowboys, football, and war. (When Remington, on assignment in Cuba for William Randolph Hearst, reported that there was no war there, Hearst allegedly responded, “You furnish the pictures, and I’ll furnish the war.”) He was already well known for his drawings and paintings when he took up sculpture in the 1890s, but now he is perhaps best known for his bronzes. He attended the art school before it offered degrees, but he was awarded one in 1900 after he submitted one of his manuscripts to Yale (and donated one of his artworks). He was only 48 when he died in 1909 of complications from an appendectomy. View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

Painter, illustrator, and sculptor Frederic Remington ’00BFA (1861– 1909) was the only truly famous artist to come out of the School of Fine Arts in its first decades. Unlike most art students of his time at Yale (1878–79), Remington was welcomed into the extracurricular world of Yale College, playing on the football team and drawing cartoons for the Yale Courant. After his father died, he left school for the American West, discovering the subject that would bring him fame. His drawings of frontier life—-including works like Bronco Buster (shown here, 1895)—began appearing in magazines like Harper’s Weekly in 1882, and he soon became a chronicler of the masculine pursuits favored by his friend Theodore Roosevelt: cowboys, football, and war. (When Remington, on assignment in Cuba for William Randolph Hearst, reported that there was no war there, Hearst allegedly responded, “You furnish the pictures, and I’ll furnish the war.”) He was already well known for his drawings and paintings when he took up sculpture in the 1890s, but now he is perhaps best known for his bronzes. He attended the art school before it offered degrees, but he was awarded one in 1900 after he submitted one of his manuscripts to Yale (and donated one of his artworks). He was only 48 when he died in 1909 of complications from an appendectomy. View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

Remington’s sculpture “The Wounded Bunkie” (1896) is an example of his narrative illustration style rendered in bronze. View full image

Yale University Art Gallery

Remington’s sculpture “The Wounded Bunkie” (1896) is an example of his narrative illustration style rendered in bronze. View full image

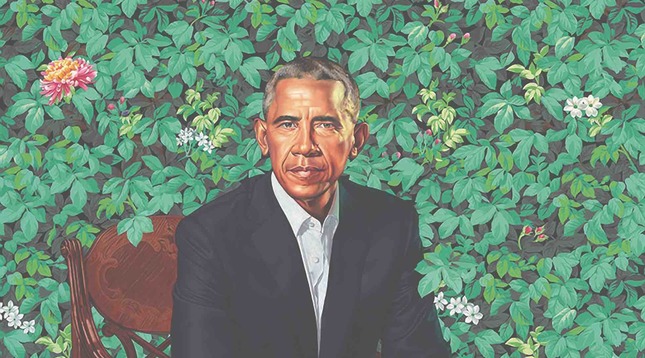

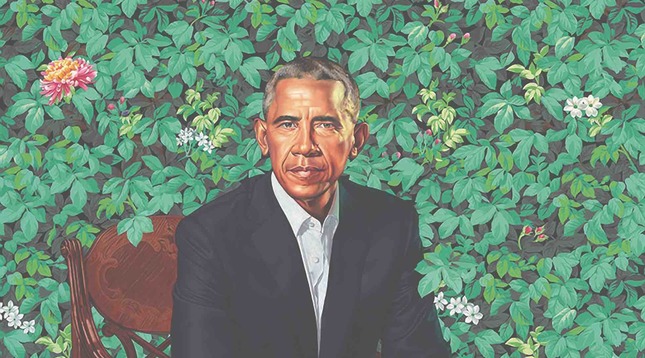

© Kehinde Wiley

Many Americans first heard of Kehinde Wiley ’01MFA (b. 1977) when his official portrait of President Barack Obama for the National Portrait Gallery (shown here) was unveiled in 2018. Critics and citizens alike pondered the symbolism of Wiley’s placement of Obama in a sea of foliage and flowers. Wiley, who grew up in South Central Los Angeles and graduated from the San Francisco Art Institute before attending Yale, made his name painting ordinary people in heroic poses inspired by “classical European paintings of noblemen, royalty, and aristocrats.” Most recently,Wiley has unveiled his first public sculpture, which comments similarly on the tradition of the classical equestrian statue in a politically charged way. Wiley’s “Rumors of War” will eventually stand in Richmond, Virginia, which is home to equestrian statues of several major Confederate figures. View full image

© Kehinde Wiley

Many Americans first heard of Kehinde Wiley ’01MFA (b. 1977) when his official portrait of President Barack Obama for the National Portrait Gallery (shown here) was unveiled in 2018. Critics and citizens alike pondered the symbolism of Wiley’s placement of Obama in a sea of foliage and flowers. Wiley, who grew up in South Central Los Angeles and graduated from the San Francisco Art Institute before attending Yale, made his name painting ordinary people in heroic poses inspired by “classical European paintings of noblemen, royalty, and aristocrats.” Most recently,Wiley has unveiled his first public sculpture, which comments similarly on the tradition of the classical equestrian statue in a politically charged way. Wiley’s “Rumors of War” will eventually stand in Richmond, Virginia, which is home to equestrian statues of several major Confederate figures. View full image

150 Years of Art

Read an essay by art journalist Robin Cembalest ’82 about the School of Art’s importance.

1 comment

Ken McKenna ‘75, ‘78 , 12:54am November 13 2019 | Flag as inappropriate